Passing the Stress Test

by Susan K. Parson, FAA Safety Briefing Editor

Human beings are amazingly diverse, but the discipline of human factors tells us that we have certain “factors of humans” in common. These include cognitive functions such as attention, detection, perception, memory, judgment/reasoning, and decision making. Such factors play a role in how we react, both physically and psychologically, with respect to a given environment, product, or experience.

When one or more of these encounters poses a challenge or demand, the universal human reaction involves some level of emotional or physical tension that we call “stress.” For that reason and a few more presented below, I tend to characterize stress as the ultimate human factor.

The Two Faces of Stress

According to Roman mythology, Janus was the god of duality, among other things. The Greek comedy and tragedy faces used to symbolize theater are sometimes called Janus masks, presumably for this reason.

Like Janus, stress is a creature of duality. Depending on the situation, the person, and even minute things like the time of day, stress can motivate, or it can debilitate. It can stimulate a helpful hyper-focus, a harmful fixation, or an equally dangerous lack of focus. It can be positive when it pushes a person to positive activities or outcomes. On the flip side, it can be negative when it causes anger, frustration, or high tension.

Another duality is that stress can take two forms. You “host” the acute version when, for example, you quickly maneuver to avoid conflicting traffic or find yourself in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) on a visual flight rules (VFR) flight. Acute stress leapt into my life on several memorable occasions, including the first time I got holding instructions while flying single-pilot instrument flight rules (IFR) in no-kidding solid IMC. Handled properly — more on that in a moment — acute stress can help you safely navigate potentially dangerous situations.

Another duality is that stress can take two forms. You “host” the acute version when, for example, you quickly maneuver to avoid conflicting traffic or find yourself in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) on a visual flight rules (VFR) flight. Acute stress leapt into my life on several memorable occasions, including the first time I got holding instructions while flying single-pilot instrument flight rules (IFR) in no-kidding solid IMC. Handled properly — more on that in a moment — acute stress can help you safely navigate potentially dangerous situations.

Chronic stress is a peskier and more insidious visitor — kind of like a lingering house guest who eats all your food, ransacks your belongings, and occupies all your favorite spots. Just as with the overstaying house guest, chronic stress may leave you seething in silence, trying to pretend all is well. Meanwhile, your blood pressure soars, you sleep poorly, and you feel like you are carrying lead weights. Unmanaged, chronic stress can do permanent damage.

The four As of stress management are: Avoid, Alter, Adapt, or Accept.

Having been there and done that, I cannot overemphasize the importance of promptly recognizing and dealing with chronic stress. Needless to say, the dark side of stress doesn’t play nicely on the flight deck if you are the pilot of an aircraft, or in the maintenance hangar if your job is fixing flying machines. But managing stress is just as important for your overall quality of life.

Identify — Friend or Foe?

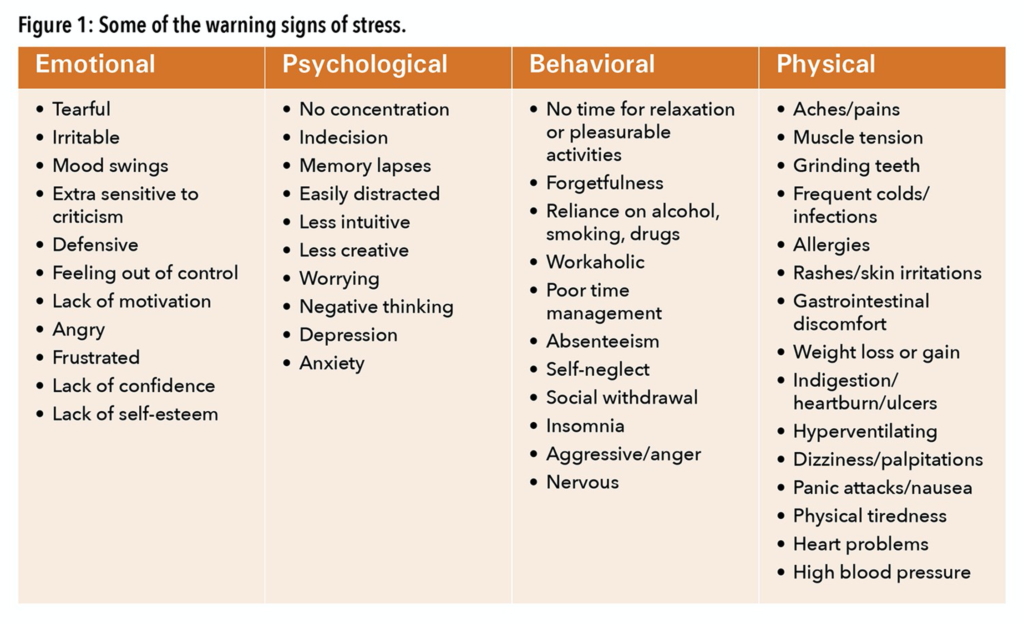

You have probably heard the term IFF, the abbreviation for Identification Friend or Foe. Briefly, IFF is an identification system that lets military and civilian ATC interrogation systems identify aircraft, vehicles, or forces as friendly. It also determines bearing and range from the interrogator. In order to manage stress so as to get the benefits of its better half while keeping its dark side at bay, you need to develop an internal IFF system to help you spot signs of stress. See figure 1 for a few things to look for.

Playing the “A” Game

Playing the “A” Game

I’ve written in previous issues that the “aviate” part of the familiar Aviate-Navigate-Communicate mantra means managing attitude, airspeed, altitude, and avionics. Because it’s easy to remember, an article on the four As of managing stress resonated strongly with me and could be helpful to you as well.

The four As of stress management are: Avoid, Alter, Adapt, or Accept.

Avoid sources of stress. Say “no” to taking on more than you can handle, whether in personal or professional situations. Limit the time you spend with people who cause stress in your life. Stop doing things that make you tense.

Alter the situation. Create a balanced schedule. Be willing to compromise. Learn to be appropriately assertive by expressing feelings and needs in an open and respectful way.

Adapt to the situation. Learn to reframe problems (e.g., a mistake is an opportunity to learn; bad weather offers time to refresh aviation knowledge). Put issues in perspective (e.g., will I remember this a month from now?). Set reasonable standards. Practice an attitude of gratitude.

Accept what you can’t change. Focus on what you can do, and don’t obsess about things you can’t control. Frame challenges as opportunities for growth and learning. Let go of anger and resentments. Confide in a trusted friend, family member, colleague, or professional.

This Too Shall Pass!

Even normal life offers myriad daily opportunities to practice stress management. At the time of this writing, though, the COVID-19 public health emergency continues to disrupt virtually every aspect of what we knew as “normal life.” I find it can be a challenge to manage stress in this utterly unprecedented time, and perhaps that is true for you as well. Let’s jointly resolve to put the four As of stress management into daily use, and remember that this too shall pass.

Susan K. Parson (susan.parson@faa.gov) is editor of FAA Safety Briefing and a Special Assistant in the FAA’s Flight Standards Service. She is a general aviation pilot and flight instructor.

Reprinted with permission from FAA Safety Briefing. Visit the FAA Safety Briefing website at:

https://www.faa.gov/news/safety_briefing/.