Sharing is Caring

How Voluntary Reporting Programs Benefit Everyone

By Jeffrey Smith, FAA Field Support Program Office

It’s a beautiful winter day with clear skies, unrestricted visibility, and no turbulence. You’re returning to your home base after getting lunch at a nearby airport. Your significant other is next to you, enjoying the benefits of your newly acquired pilot certificate. Full of fresh barbeque, relishing the awesome weather, and sharing this flight with your loved one, you think — what could go wrong? You’re a few miles from your destination, which lies underneath Class B airspace. You look at your GPS (with data link to your transponder/ADS-B) and see a “Transponder Failed” message. Questions flood your mind. How long has the transponder (and perhaps ADS-B) been inoperative? Are you in regulatory violation? Will you get a call from the FAA? And why has this perfect flight been marred by a failure in technology?

This hypothetical scenario can help us understand the interface between voluntary reporting programs and the FAA’s Compliance Program. We’ll also see how these initiatives can benefit you in this kind of situation. Let’s start by reviewing some background information.

Foundations of Safety

The Compliance Program has been around for about nine years now, but the foundations of the program have been around for much longer. This includes the various voluntary reporting programs, which have long recognized the value of a transparent exchange of safety-related information. The Compliance Program takes the concepts of voluntary reporting programs and makes the general benefits available to all participants in the National Airspace System (NAS).

Trying to ignore or cover up safety issues is antithetical to the concept of sharing and does nothing to advance aviation safety. And in many cases, it can result in a negative outcome. Examples of this include not reporting damage to a rental aircraft, which would pass that risk along to the next renter, or a close encounter between a crewed aircraft and a drone near an airport. In the case of the close encounter, you may be reluctant to report the event for fear of scrutiny by the FAA over your altitude or presence in that area. However, failure by you and others to report such events allows drones and other operators in that area to have future flights in dangerous proximity to each other. The risky situation may continue until a mid-air collision occurs.

Volunteering Data

This is where the voluntary programs come in. While the details vary per program, in general, they allow for reporting an event without fear that the information will be used against you. A report that meets applicable criteria also provides certain protections from a legal enforcement sanction. In return, the FAA receives safety information that people would otherwise be reluctant to share. This information helps identify safety issues, informs where resources need to be focused, and indicates if specific outreach to the aviation community is needed.

Perhaps the most familiar voluntary reporting mechanism for general aviation (GA) is the Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS). Dating back to 1975, it is also the longest running of the programs. ASRS is often colloquially referred to as “NASA reports” due to NASA receiving and processing the data before any information is sent to the FAA. A report can be filed by anyone to express a safety issue, even if it involves a regulatory violation. NASA will review the information and provide proof of receipt. The personally identifying information will not be shared outside of NASA, including with the FAA, unless the report involves criminal activity or an accident. Further, if the event became known to the FAA by some other means and the FAA takes legal enforcement action, then the FAA will not impose any civil penalty or certification suspension if certain criteria are met.

Sharing is Good

In all that we do as participants in the NAS, safety should be at the forefront. The use of voluntary reporting programs, such as ASRS, is no exception. We should be reporting information primarily for the benefit of safety, and we should approach any reporting with that mindset. While there are protections afforded by the voluntary programs, we should not view them as “get-out-of-jail-free” cards. Rather, they are another tool in an overall safety toolbox that creates a net benefit for everyone.

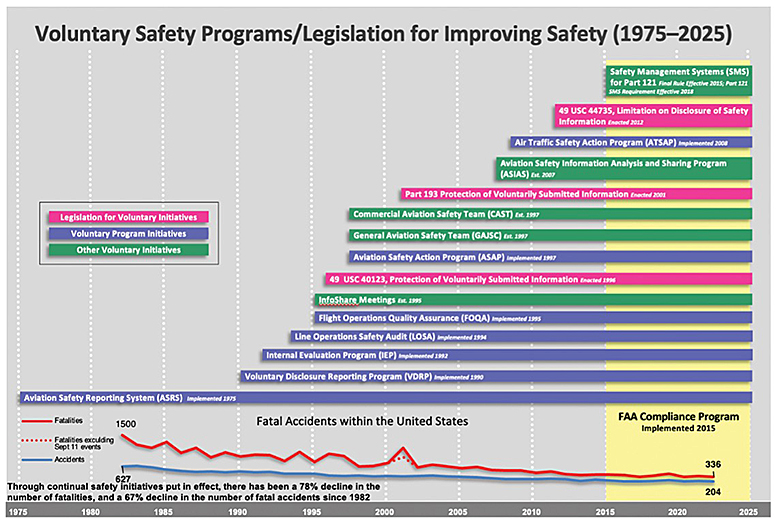

The FAA believes that using these tools has a positive impact on safety. The timeline of voluntary reporting programs, legislation, and other initiatives (see figure 1) shows the number of fatal accidents and fatalities, and we see a general decline for both over the past several decades. While there are many factors that contribute to the accident rate, and correlation does not equal causation, it certainly does appear that the voluntary programs and related initiatives are contributing positively to aviation safety.

Figure 1: The FAA believes that voluntary reporting programs, legislation, and other initiatives are having a positive impact on aviation safety.

The information you provide in an ASRS report may be used to identify safety trends that can be a catalyst for action, such as FAA Safety Team (FAASTeam) messaging. The information is also used by industry/government cooperative partnerships such as the General Aviation Joint Safety Committee (GAJSC). This group looks at a variety of information to develop safety enhancements. These safety enhancements compel action on the part of the FAA and aviation advocacy groups to address identified safety concerns. FAASTeam educational outreach and GAJSC safety enhancements are examples of how information from voluntary reporting can be used to make data-informed decisions to best focus resources and make improvements to the NAS.

Beyond GA

While this article focuses on the reporting and initiatives most familiar to the GA community, there are other voluntary reporting programs. The Aviation Safety Action Program (ASAP) is used by pilots, mechanics, flight attendants, ground personnel, and others working for commercial operators. The Voluntary Disclosure Reporting Program (VDRP) is used by management at many air carriers and repair stations. Both ASAP and VDRP, along with other voluntary programs, have the same basic tenets — identify safety issues and take action to prevent future problems. And, as a parallel to the GAJSC, the Commercial Aviation Safety Team (CAST) works to address risk in the commercial aviation sector.

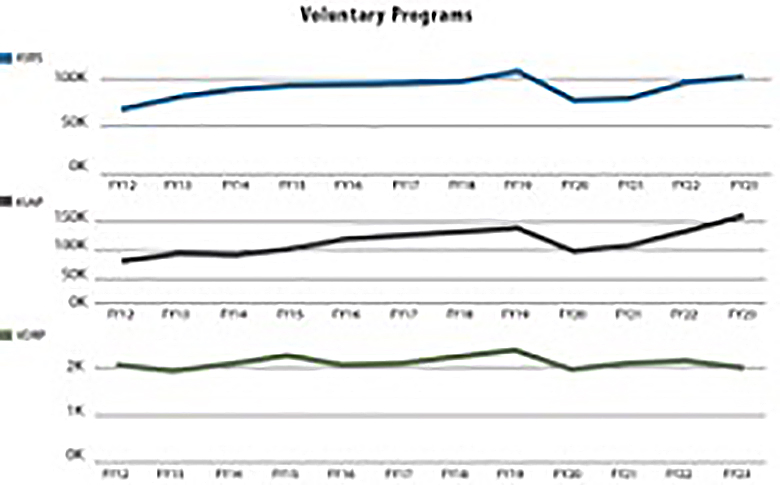

The numbers of voluntarily submitted reports into ASRS, ASAP, and VDRP have been on the rise over the past several years including the era of the Compliance Program (except at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic). The FAA believes this shows that the aviation industry and community continue to see the value in sharing information through voluntary reporting programs.

Figure 2: The voluntary reporting numbers for the ASRS, ASAP, and VDRP

have been on the rise over the past several years.

To Report or Not to Report

Now that we’ve taken an in-depth look at the voluntary reporting programs, let’s return to the example of the transponder failure from the beginning of this article.

Despite the initial shock, fortunately, you are an avid reader of the FAA Safety Briefing and aware of the FAA’s Compliance Program and the just safety culture approach the agency takes towards safety deviations. Your panic subsides and you consider your options. You are already well inside the overlying shelf of the Class B and near your destination, which is the closest airport relative to your current position. You decide it makes sense to continue home. You also figure that it may be best to try and have your ADS-B Out functioning prior to entering the traffic pattern. You recycle the GPS-integrated unit by turning it off and then back on. The technology comes back to life, and you get that familiar indication of the transponder output. You land without further incident.

Out of curiosity, you check an online flight tracking website to see your flight path. You note that it shows your takeoff from the airport where you had lunch, but the trail drops off after 20 miles. You conclude that’s where the transponder and ADS-B likely failed. You also do some mental calculations to determine that you went about 10 minutes before noticing the failure and that the failure occurred outside the 30 nautical mile Class B ring. This could indicate a deviation from 14 CFR part 91, sections 91.217 and 91.225.

You want to make certain that such an event does not happen again. You think the transponder failure was a glitch, and while you intend to be vigilant for future failures, your biggest worry is that you were unaware of the failure message. You plan to add the GPS message area to your normal flight instrument and engine indicator scan. You also plan to check the GPS for functionality, and for any traffic between you and the airport, prior to entering that 30 nautical mile ring. So, you have a good plan moving forward to improve procedures and prevent reoccurrence, which are expectations under the Compliance Program.

Wanting to contribute to the safety system, you determine that filing an ASRS report would be beneficial. You go to the website listed in the Learn More section below and find the link for an electronic report submission. You complete the report and ultimately receive the confirmation from NASA. As this was not an accident or criminal activity, you know that NASA will not share your name or the specific details of this event with the FAA. You also know that if there are several similar events reported through ASRS, additional systemic actions may be recommended. You also retain the reporter identification strip returned to you by NASA in case it is needed for future reference.

There is a possibility that the local FAA Flight Standards District Office (FSDO) may reach out to you about the flight. The FSDO may have received information from the Class B air traffic control facility, and an aviation safety inspector could contact you as part of a routine investigation. This would be handled under the Compliance Program and the FAA’s just safety culture foundations. Based on the details of the event and the lack of negative historical records, it is likely the event would be addressed with a compliance action (perhaps counseling). If, however, the details of the event caused the FAA to take legal enforcement action, any sanction imposed by the FAA (e.g., a 30-day certificate suspension) would be waived assuming the required parameters are met. The finding of a violation would be on your record; however, you would not have to serve the suspension.

You Made a Difference

As you can see, there are benefits on multiple levels to contributing to the voluntary reporting programs. You are encouraged to become familiar with the programs that apply to you. In this way, you can protect yourself, potentially benefit others, and in all cases be an active participant in improving aviation safety.

Jeffrey Smith is the acting manager of the FAA’s Field Support Program Office. He holds an ATP certificate, is a flight and ground instructor, and is an A&P mechanic.

Reprinted with permission from FAA Safety Briefing. Visit the Flight Safety Briefing website:

https://www.faa.gov/news/safety_briefing/