It’s All in Your Approach

Top Tips to Fine Tune a Final Approach and Landing

By Tom Hoffmann, FAA Safety Briefing Magazine Managing Editor

You’re almost there. On your culinary quest for the perfect midday meal, you successfully navigated a non-routine taxi clearance, nailed a perfect takeoff, and enjoyed an exciting and happily uneventful cruise portion of your flight. The only thing left is to fulfill that inevitable Newtonian principle: what goes up, must come down — smoothly and hopefully in one piece. So before you sink your teeth into that juicy airport diner cheeseburger deluxe, you must carefully set the table for a successful landing. Let’s take a look at some ways to fine tune your approach and get you on your way to culinary bliss — or whatever other happy diversion might bring you to your destination.

Maintain a Stabilized Approach

Have you heard these words before? Well, it’s not just a buzz term in aviation safety. It’s a critical lifesaving way to approach every flight since most landing accidents are caused by — you guessed it — an unstabilized approach. The General Aviation Joint Safety Committee also found cause to highlight the importance of this subject in its list of safety enhancements (SE) that are designed to prevent or mitigate leading accident causal factors. After an extensive review of accident data, the committee’s Loss of Control Working Group developed an SE focused squarely on promoting and emphasizing the use of a stabilized approach and landing.

So what exactly is a stabilized approach? A pilot is flying a stabilized approach when they establish and maintain a constant angle glidepath towards a predetermined point on the landing runway. Every runway is unique, but a commonly referenced optimum glidepath follows a 3:1 principle or descent ratio. This means that for every 3 nautical miles (nm) flown over the ground, the aircraft should descend 1,000 feet, simulating a 3-degree glideslope.

3:1 — Keeping the Odds of Safety in Your Favor

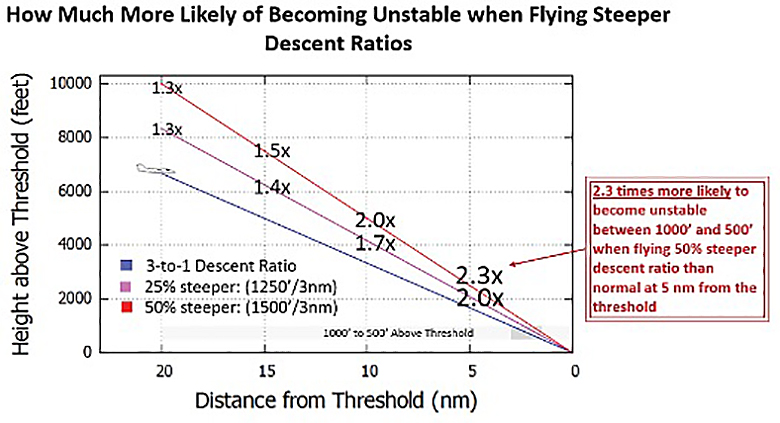

Further evidence of how important a proper descent ratio is during approach was revealed during a high-energy approach analysis performed by the Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing (ASIAS) program, a collaborative government and industry initiative. The study compared actual stable and unstable approaches of business aviation operators to the common 3:1 descent ratio from four distinct distances from the runway: 20, 15, 10, and 5 nautical miles from touchdown. Flights that were above the 3:1 descent ratio, and not stable, often had high rates of descent and high approach speeds. The analysis showed that when a flight is above the optimum 3:1 descent ratio (even at 20 nautical miles from touchdown), the approach is more at risk of being unstable when closer to the runway (i.e., 500 feet to 1000 feet height above touchdown). In fact, the study showed that chances of being unstable can double as you increasingly fly above a 3:1 flight path profile (see figure 1).

Figure 1

To help you stay on a 3:1 glidepath, estimate your descent rate by multiplying your groundspeed in knots by five (e.g., 90 knots x 5 = 450 feet per minute descent rate). Or halve your airspeed and add a zero at the end (e.g., 100 knots / 2 (+ 0) = 500). To determine your appropriate altitude for a 3-degree approach on final, multiply your distance from the runway by three, add two zeroes, and add the touchdown zone elevation. For example, if you’re three miles out with a touchdown zone elevation of 100 feet, your calculation would be: 3 (miles) x 3 = 900 + 100 = 1,000 feet). This will help you cross the runway threshold at 50 feet and hold your aiming point for the flare. You can also use a visual approach system such as a VASI or PAPI, or a precision instrument approach to help maintain a proper glidepath.

The Need for Speed

Of course airspeed plays an important role with a stabilized approach and landing too. Pilots should be familiar with the appropriate pitch and power settings required to execute different types of descents. The key to maintaining balance and order during descent is recognizing the need to offset surplus thrust — caused by the reduction in lift and induced drag — by decreasing power.

Having accurate control of both descent angle and airspeed will allow pilots to achieve the objective of a stabilized approach, which is reaching a desired touchdown point (ideally the center of the first third of the runway) with a minimum of floating before touching down. On approach, power and pitch attitude are adjusted simultaneously as necessary to control the airspeed and the descent angle, or to attain the desired altitudes along the approach path.

If the approach is too high, lower the nose and reduce the power. When the approach is too low, add power and raise the nose.

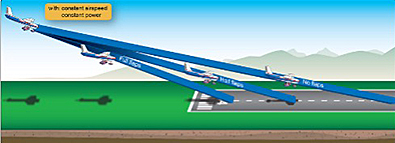

Flaps can also assist with power management on approach. The increased drag from flaps allows you to have a steeper descent angle without an airspeed increase. Just remember that incremental flap deployment allows for smaller adjustments of pitch and power. See figure 2 for a visual on how flaps can affect your approach angle.

Figure 2

The Eyes Have It

Understanding and practicing proper traffic pattern procedures is critical to your safety as well as the safety of your fellow pilot. Know your airport’s traffic pattern, especially when there are parallel runways in use. Observe and listen intently for where other pilots are operating in the vicinity. Scan for traffic using short, regularly spaced eye movements that bring successive areas of the sky into the central visual field. Each movement should not exceed 10 degrees, and each sky segment should be observed for at least one second to enable detection. This slow and steady approach helps compensate for the limitations the human eye has in being able to detect targets. To help make yourself easier to detect (and avoid), turn your lights on.

Pilots and flight instructors may also find it helpful to review a recent GAJSC study on midair collisions that shows particular locations and routes at 50 U.S. airports where collision risk may be more likely. (See the report here.)

Is That My Runway?

Ok, so you’re right on target with your airspeed and glidepath during your approach, but imagine the feeling of dread when discovering the numbers on the runway are not what you were expecting. Or worse, there are no numbers and you’ve lined up on an active taxiway! Worse yet, your 3,000-foot runway seems to have grown several thousand feet as you realize you’re approaching the wrong airport. It happens, and more frequently than you might think. Wrong surface events like these can be extremely deadly. The good news is there are lots of red flags and tools that can help you avoid them.

Everything from an airport’s size, to runway layout, to activity levels, can contribute (sometimes in concert) to leading a pilot astray. Parallel runways seem to be among the most common triggers for mistaken identity. Often a shorter and narrower parallel runway can get overlooked by a pilot approaching an airport and be mistaken as a taxiway. A different colored surface on each of the runways can add to the confusion.

Parallel runways can also be staggered laterally and horizontally, sometimes by several thousand feet. A pilot cleared to land on a 3,500-foot Runway 36R may not notice it is much further apart and set back than its 36L sibling — with the latter’s clearly marked threshold, touchdown zones, and 8,000 feet of roomy space luring you to land. On the flip side, sometimes an adjacent taxiway can have the same effect, especially when offset parallel runways are in place. What you might think is 36R is actually a taxiway for 36L. The real 36R could be offset further back and harder to discern. The blue taxi lights on “36R” should give away the fact that it’s not a runway, but that’s not always a given with someone who’s already mentally committed to land.

Consider also how Mother Nature can impact a pilot’s ability to correctly discern the right runway. Glare from the sun and wet pavement, snow cover, and fog can all make a landing (or departure) much more challenging. Always check the weather and try to anticipate any visibility restrictions that could present problems at your destination. If your arrival at a new destination has you approaching right before sunset on a due west heading, consider rearranging your arrival time so it is easier to pick out the correct runway, or for that matter, the correct airport.

To avoid lining up at the wrong airport, use nearby geographic features or landmarks to your advantage. Is your airport due east of a lake or large factory? In addition to reviewing your sectional chart, Google Earth maps can give you an excellent bird’s eye view of what to expect on arrival, including other area airports or features that could appear to be airports (e.g., drag strips, a closed road, a well-lit main street).

Another best practice to confirm you have the right airport (and runway) is to use any and all cockpit instrumentation and navigational aids at your disposal. Even if you’re VFR, dial in an approach and/or use GPS to confirm your position (set up a GPS waypoint on the assigned landing runway). When you’re cleared for landing, double check that you are using the runway assigned, not just what you expected to be in use. If you are ever in doubt of your approach or landing, perform a go around and promptly notify ATC.

Also be sure to make use of the FAA’s many tools and resources to help you stay on track. The From the Flight Deck video series now has over 100 videos highlighting helpful departure and arrival tips at airports all across the nation, including a new set of videos that cover operations at airports with complex geometry. The FAA’s Runway Safety Pilot Simulator has several training scenarios that highlight the many contributing factors to wrong surface events.

A green airport icon indicates a current video. A blue airport icon indicates a video coming soon.

This shows the latest “From the Flight Deck” video. Click on the hamburger icon in the upper right to view all the videos in the playlist and select it to play here.

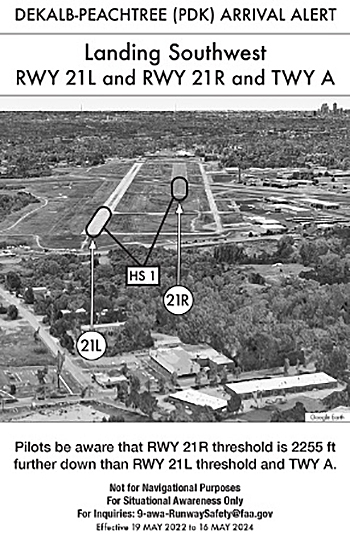

Another tool is the new Arrival Alert Notice (AAN) which visually depicts the approach to a particular airport with a history of misalignment risk. There are currently 11 AANs listed here.

The new Arrival Alert Notices visually depict approaches with a history of misalignment risk, like the staggered parallel runways seen here at PDK.

That’s the Brakes

While you may have greased the touchdown and can see the airport diner on the horizon, your landing is not quite done. There’s still the matter of braking and safely exiting the runway. Boldmethod.com provides six important braking tips in the article here. Of note is the emphasis on maximizing aerodynamic braking instead of relying on just your mechanical toe brakes. The FAA’s Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (chapter 8) advises pilots to hold back-elevator pressure to maintain a positive angle-of-attack after the main wheels make initial contact with the ground, and to hold the nose wheel off the ground until the airplane decelerates. Then, as the airplane’s momentum decreases, back-elevator pressure is gradually relaxed to allow the nose wheel to gently settle onto the runway.

Once the nose wheel is on the ground and directional control is established, carefully apply the brakes. Maximum brake effectiveness is just short of the point where skidding occurs. Be wary of how a tailwind or a wet runway can affect your landing rollout and braking effectiveness. FAA Advisory Circular 91–79A, Mitigating Risks of a Runway Overrun Upon Landing, provides guidance on how pilots can mitigate risks associated with a runway overrun, including hazards like contaminated runways, high density altitude, or excess airspeed.

With your airplane safely parked and secured, you are free to proceed to a well-deserved meal. Funny how that burger tastes a little better after a safe and smooth landing. Bon appetit!

Tom Hoffmann is the managing editor of FAA Safety Briefing. He is a commercial pilot and holds an A&P certificate.

Reprinted with permission from FAA Safety Briefing. Visit the Flight Safety Briefing website: https://www.faa.gov/news/safety_briefing/.