Making It Count

How Aircraft Transponder Signals Take the Guesswork Out of Counting Non-Towered Airport Operations

By Jennifer Caron, FAA Safety Briefing Copy Editor

“Many of the things you can count, don’t count. Many of the things you

can’t count, really count.”— Albert Einstein

“I always feel like the runway is just long enough to keep me alive,” one pilot comments on Reddit. Small taxiways, rough, bumpy runways, and insufficient signage are some of the frustrations pilots have expressed over the less than ideal conditions they’ve encountered, and would like to see improved, at some of the nation’s general aviation (GA) airports.

When it comes to a funding decision on airport investments, there are many elements involved. According to the National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS), airport capital development needs are driven by current and forecasted traffic, use and age of facilities, and changing aircraft technology, to name a few.

But one important part of the decision puzzle is the total number of aircraft operations that happen at the airport. Aircraft operations counts are a key element in the overall criteria used to inform decisions on aviation systems and airport master planning, particularly for environmental studies and aviation forecasts, as well as airport design and funding. To borrow from Einstein’s quote above, Accuracy Really Counts! Accurate and complete numbers inform the decisions that will rehabilitate those runways and taxiways, add that airfield signage, and smooth out that rough and bumpy surface.

So what are aircraft operations counts, and who’s doing the counting?

The ATCs of 1–2–3s

Aircraft operations are defined in Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) section 170.3 as the airborne movement of aircraft in controlled or non-controlled airport terminal areas. There are two types of operations: local and itinerant. Local operations are aircraft in the local traffic pattern, or in local practice areas, either within sight or at a 20-mile radius of the airport, and that includes touch-and-go landings. Itinerant operations take into account all the other non-local operations.

At airports with air traffic control (ATC), controllers track and record aircraft activity. With dedicated processes and personnel in place to count aircraft operations, it’s more likely that the data collected is both accurate and complete. However, the vast majority of airports in the U.S. do not have ATC personnel to count aircraft activity. So who’s counting the aircraft at those small, non-towered GA airfields, which often lack an on-site manager or fixed-base operator to take the count?

Current counting methods for non-towered airports varies in both accuracy and reliability.

Let Me Count the Ways

When I first learned that aircraft operations counts take place at non-towered airports, I immediately pictured some random guy sitting just off the flight line in a green lawn chair, binoculars slung around his sunburned neck, punching a hand-held counter for every takeoff and landing he could see. Obviously, that’s not really how it’s done, but that image is not too far off the mark.

Current counting methods for airports without ATC varies in both accuracy and reliability. The number and type of operations is often determined by the “best guess” of the airport manager, or based on prior-year counts estimated to the current date. The data is not standardized and the results are hodgepodge at best, making it difficult to compare data from one airport to another or to use the counts for high-confidence decision making.

Insufficient knowledge about aircraft activity at non-towered airports continues to be a concern for aviation agencies at both state and federal levels. A study by the Airport Cooperative Research Program found that many state aviation agencies, and some airports and planning organizations, have developed aircraft traffic counting programs to track airport activity, but with mixed results.

The FAA provides guidance on documenting aeronautical activity, including the number of operations by aircraft, in Advisory Circular 150/5000–17, Critical Aircraft and Regular Use Determination. Sources include aircraft landing fee reports, reliable aircraft logs recording aircraft make and model, data from commercial flight trackers, and completed instrument flight rules (IFR) flight plan data entered in the FAA’s Traffic Flow Management System Counts (TFMSC) database.

“I can’t say there’s one predominant way airports do their traffic counts,” says Michael Lawrance, Senior Aviation Planning Specialist in the FAA’s Airports Planning and Environmental Division. “The use of TFMSC is a usual go-to source, but that only gets you aircraft that flew to your airport IFR, which typically accounts for about 25% of total operations.” Kent Duffy, FAA Operations Research Analyst notes that “the TFMSC data is often sufficient to understand the need for a longer runway since the majority of business jets and large turboprops fly under IFR the majority of the time. However, the total operations data is still needed for aviation forecasts and the environmental studies needed to extend a runway.”

Other methods include counting traffic year-round, sampling traffic seasonally to estimate annual operations, multiplying a pre-determined number of operations per based aircraft by the total aircraft based at the airport, performing regression analysis, and asking the airport manager — often the most used, and least accurate way to collect traffic counts. So can you picture the guy in the lawn chair now?

“Some airports supplement their data with fuel sales logs, FBO records, flight school activity, ‘conversations with the airport manager,’ or comparisons of other airports in the region,” Lawrance explains. Other methods such as automatic acoustic counters, video devices, and pneumatic counters are not long-term solutions due to their expense and the impracticality of deploying these devices on a large scale. However, beyond the IFR data captured by TFMSC, many of these methods vary in both reliability and accuracy, resulting in low-confidence data.

“While many of those methods are fine for local planning purposes, they are not accurate enough for us to use in project justifications, primarily capacity-related projects,” Lawrance explains. Relevant capacity projects that necessitate accurate total operations counts include new Federal Contract Towers or secondary runways to reduce congestion.

You Can Count On It

Research and innovation answers the call. PEGASAS looked at using signal strength obtained from aircraft transponders to accurately register operations counts. This technique is both innovative and economical, since it would re-purpose shelf-stable technology to address the need.

In 2016, Purdue University developed a transponder signal-counting technology to register operations with extended Mode S aircraft transponder signals. These signals are received with a 1090 MHz software-defined radio platform and contain global positioning system (GPS)-derived aircraft position information.

Mode S data captured includes unique ID, GPS latitude and longitude, elevation, and signal strength. This data is used to calibrate a model that has altitude and signal strength as inputs to estimate arrival and departure operations.

In 2017, the FAA tasked Purdue University under PEGASAS, the Partnership to Enhance General Aviation Safety, Accessibility, and Sustainability, an FAA Center of Excellence with a national network of researchers, educators, and industry leaders, to further evaluate an accurate, cost-effective means of conducting operations counts at non-towered airports using Mode S. The collaborative FAA/PEGASAS research team includes Jonathan Torres in the FAA’s Airport Safety Technology Research and Development division at the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and university leads Darcy Bullock and John Mott at Purdue University.

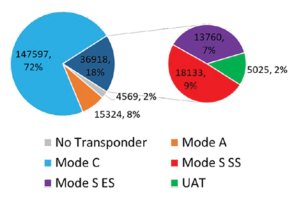

The FAA required that most domestic aircraft operating in rule airspace be equipped with either Mode S, 1090 Extended Squitter, or Universal Access Transceiver (UAT) ADS-B transponders by January 1, 2020. The majority of GA aircraft are now equipped with ADS-B. However, there is a substantive share of GA aircraft that don’t operate in rule airspace that still have only Mode C transponders. Not a problem since this novel, data-capturing technology uses an inexpensive ground-based radio receiver to monitor both Mode S and Mode C data and can easily obtain signals in a passive manner with no adverse impacts on aircraft communication or sensitive equipment.

Pole-mounted Version II device installed at Terre Haute Regional Airport (KHUF) for data collection at a towered airport. Stand-alone Version II device installed at

Indianapolis Executive Airport (KTYQ) for data

collection at a non-towered

To test and validate the transponder signal concept, the PEGASAS research team developed two versions of a signal counting device that monitors aircraft transponder data to count aircraft operations. Devices were deployed at four GA airports in Indiana, two towered and two non-towered. Version I devices (an experimental transponder signal receiver and processing system) were installed at the two towered airports: Purdue University Airport (KLAF), and Terre Haute Regional Airport (KHUF). Version II devices (a pre-production prototype of the transponder signal-counting technology) were installed at both towered airports and at two non-towered airports: Indianapolis Executive Airport (KTYQ), and Warsaw Municipal Airport (KASW).

These devices collected over 150 million transponder records to produce regular operations counts over different time periods, from 8 to 180 days. The operations counts calculated from these records were compared with those obtained from the FAA Air Traffic Activity Data System (ATADS) database, which contains official operations data reported by air traffic control towers at airports.

The accuracy of operations counts from the Version I devices ranged from -10.2% to 7.6%, as compared to the ATADS counts. The differences between ATADS and estimated operations counts from Version II ranged from -3.1% to 3.0%. The test results suggest that the new method of counting operations counts based on transponder signal data is more accurate than most of the other methods currently in use at non-towered airports. Overall test results indicate that the transponder signal-counting technology is an accurate and cost-effective way to count non-towered airport operations.

The majority of GA aircraft are now equipped with ADS-B. However, there is a substantive share of GA aircraft that don’t operate in rule airspace that still have only Mode C transponders. This project uses an inexpensive ground-based radio receiver to monitor both Mode S and Mode C data. Image courtesy of PEGASAS

The Final Countdown

It’s a winning concept, and generates cost-effective, accurate, and detailed operations counts. A transportation data services company called Quality Counts has already bought the license for this novel technology and has a product.

Looking ahead, the data collection continues. Further research involves refining the overall process to ensure the greatest possible accuracy in the count registration, including a means to gather more data, such as aircraft type. This information can provide additional insight to airport managers about the fleet mix of aircraft operating at their airports.

Set your clocks and stay tuned for updates on this exciting new technology.

Jennifer Caron is FAA Safety Briefing’s copy editor and quality assurance lead. She is a certified technical writer-editor in the FAA’s Flight Standards Service.

Reprinted with permission from FAA Safety Briefing. Visit the Flight Safety Briefing website: https://www.faa.gov/news/safety_briefing/.