SPLAT! The Story of Snarge —

Accidental “Meetings” Between Aircraft and Wildlife

By James Williams, FAA Safety Briefing Associate Editor

Snarge: (snärj) n. It’s the word used for what remains of a bird after it strikes an aircraft. It’s not pretty … and neither are the results of most bird collisions with aircraft, which seem to be increasingly common. Anecdotes abound. On a recent road trip with an old friend who happens to be a regional jet captain, talk turned to hangar flying. “I seem to be having a lot of bird strikes lately,” he said. In the wake of US Airways Flight 1549’s miraculous landing in the Hudson River more than a decade ago, public attention focused sharply on one of aviation’s most chronic problems: wildlife strikes. As my friend reported, “One strike on landing was so bad we had to take the aircraft out of service and ferry it back to the manufacturer, unpressurized. The birds did enough damage to the pressure vessel that we didn’t want to risk it.”

That was a wise decision. A 2019 accident in Florida proved that point. On approach to Naples Airport, a Piper Twin Comanche entered an unannounced turning decent and crashed, killing the sole pilot on board. As far as air traffic controllers could tell, the flight was completely routine, right up until the pilot deviated from his flight path. The National Transportation Safety Board determined that the cause of the accident was a loss of control due to a bird strike with a black vulture, based on the remains found inside the wreckage of the aircraft.

A Growing Concern

Just how big is the problem?

Although serious events are rare, wildlife strikes can happen nearly every day. Air traffic controllers handled over 87,000 pre-COVID flights per day (commercial passenger, general aviation, air taxi, air cargo, military) during which there were 17,358 strikes documented in 2019. That equates to about 48 strikes per day, or one strike for every 1,812 flights. The important statistic to remember though is that there were only 739 strikes recorded in 2019 with any level of damage, meaning there were only two damaging strikes per 43,500 flights.

Over the past 20 years, the problem of wildlife strikes has only gotten worse. According to the U. S. Department of Agriculture, 13 of the 14 largest bird species have shown significant population increases. These include Canada geese, white and brown pelicans, sandhill cranes, wild turkeys, and bald eagles. Populations of many other hazardous species, such as turkey vultures, snow geese, red-tailed hawks, ospreys, great blue herons, double-crested cormorants, and white-tailed deer have also increased dramatically. Adding to the challenge is the fact that most of these species have adapted to living in urban environments, including airports.

Wildlife strikes are one of the most pressing concerns we face at U.S. airports.

Experts put the total losses of wildlife strikes at $196 million per year in direct damage and associated costs, and over 110,000 hours of aircraft downtime. In an industry that runs on razor thin margins at virtually every level, these losses could be crippling. Financial losses pale in comparison with the loss of life that occurs in some wildlife strikes. While birds make up 94% of those strikes, they aren’t the only problem. Between 1990 and 2019, there were 1,211 reported deer strikes in the U.S.

“Although strike reporting has increased significantly during the last two decades, there are reporting gaps from certain airports and airlines that need to be filled,” says the FAA’s National Wildlife Biologist John Weller. “Larger, part 139 airports, and those with well-established wildlife hazard management programs, have reporting rates about four times higher than other part 139 airports.”

“Furthermore,” Weller says, “GA airports that are part of the National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS) comprise only 15% of the overall strikes reported into the database, yet have accounted for 64% of reported civil aircraft destroyed or damaged beyond repair due to wildlife strikes from 1990 to 2020.”

“Despite reporting gaps, both the quality and quantity of strike reports being submitted have steadily increased,” says Weller, “but we can still do better.” Weller points out that species identification is only provided in about 60% of all reported strikes and that the estimated and/or actual cost of the strike event is typically not provided. According to Weller, both are “critical pieces to understanding a complicated puzzle.”

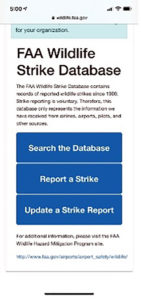

With this in mind, Weller, and his FAA wildlife biologist colleague Amy Anderson, have laid out steps to improve the reporting process. “We’ve worked hard to make reporting a strike as easy as possible. We’ve got a website, and we have now made it possible for you to report wildlife strikes directly from your smartphone at wildlife.faa.gov. We are always striving to get the word out to pilots as much as possible.”

What Can I Do?

What Can I Do?

Anecdotes are not enough to get a handle on the true magnitude of the issue. As Weller observes, the biggest challenge for airport wildlife managers today remains the need for good strike data as well as mitigating hazardous wildlife (and their attractants) off airport properties.

To improve that data, the FAA has worked to make reporting wildlife strikes much easier. Simply navigate to: wildlife.faa.gov and click “report a strike.” As noted earlier, you can even do it from your smartphone.

The form also includes instructions for safely collecting remains whenever possible. Though admittedly distasteful, the remains are critical to helping airport wildlife managers create better mitigation strategies. These strategies differ according to species. For instance, the methods used to drive off a hawk are different from those that would be effective against a starling. As outlined on the website, the remains — generally feathers — should be sent to the Smithsonian, which provides identification services free of charge to U.S. registered aircraft owners and operators. If feathers are not available, even a swab of the biological material (a.k.a., snarge) can help experts determine the species through DNA.

If we all pitch in and help improve the data, we can create safer skies through better mitigations.

Propane “noise cannons” are a common tactic to encourage birds and other wildlife not to gather on the airport.

Learn More

🐦 FAA Wildlife Hazard Mitigation

🦆 FAA’s The Air Up There Podcast: Flora, Fauna, and Flight

🦚 Smithsonian Institute’s Feather Identification Lab

🦩 Guidebook for Addressing Aircraft/Wildlife Hazards at GA Airports

🦃 FAA Wildlife Hazard Mitigation Video:

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in our Nov/Dec 2011 issue but has been extensively updated with current information and statistics.

James Williams is FAA Safety Briefing’s assistant editor and photo editor. He is also a pilot and ground instructor.

Reprinted with permission from FAA Safety Briefing. Visit the Flight Safety Briefing website: https://www.faa.gov/news/safety_briefing/.