To Balk or Not to Balk, that is the Question. (Hamlet)

And if so, how to do it better.

By Hank Canterbury

Why do so many Loss of Control [LOC] incidents / accidents happen on takeoff or during a go-around?

The Airplane Owners & Pilots Association [AOPA] conducted a study of LOC accidents in the traffic pattern. Contrary to what most pilots think, AOPA found that 89% of LOC accidents occur during or right after takeoff, rather than on base-to-final (e.g., skidding turn, stall and spin). A surprise aircraft pitch up (trim stall?) may be one of several reasons for these accidents; however, let’s explore this more.

First off, most of us don’t practice go-arounds or balked landings very often. Then, when we are required to perform one, it is usually a last-minute decision that is rushed. Therefore, we are surprised by the strong reaction of the plane when full power is quickly applied. The plane will not be in the usual takeoff configuration — nor will it be trimmed for that condition. When power is applied, it creates a very different reaction than we are accustomed to on a normal takeoff.

Here is something else to consider: Why is the decision to go around delayed or avoided? Perhaps somewhere in your experience, you may have been told, absent an obvious conflict on the runway, that making a go-around is embarrassing evidence you didn’t fly the approach as well as you normally do and you may be in for some sniping or razzing from the airport gang. If you suffer this misplaced guilt, get over it: it’s simply not true!

Go-arounds or balked landings are a basic and necessary piloting skill to have in your tool kit, just like other maneuvers. Use it freely and whenever there is any doubt about how things are going.

Regardless of why you may need to go around, it is important to note the changes in aircraft trim that have occurred as you approach a landing. Don’t forget: these changes will cause different aircraft reactions than what you may expect when you apply full power. Realizing why these forces and reactions occur begins the journey to corrective action. A little practice will smooth things out.

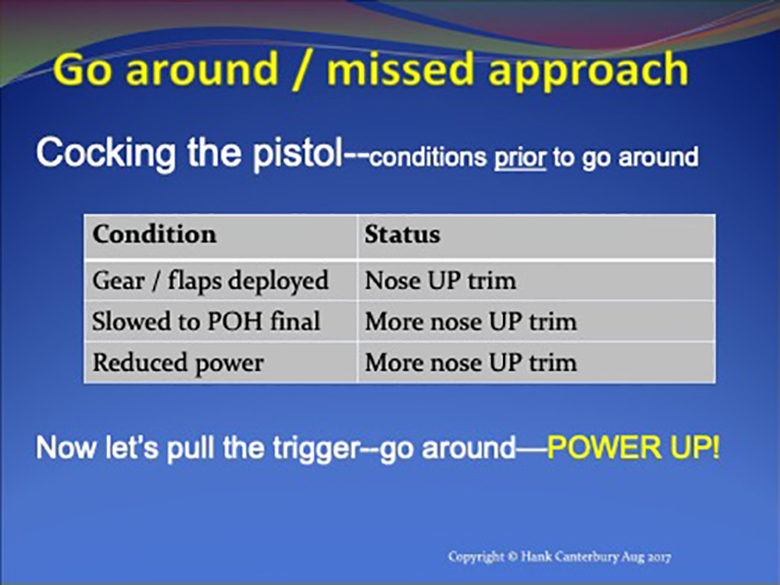

In one of my “Loss of Control” presentations in BPT Clinic I call it “Cocking the Pistol.”

As you approach a landing, you make changes in configuration, speed and power. That sets up what I call the “Cocked Pistol,” just waiting for the trigger to be pulled. That is the moment at which the power is suddenly increased to full available. Now the plane reacts just like it thinks it is supposed to. However, you are startled and dismayed by the sudden, forceful pitch up, as well as a big yaw in a single engine aircraft.

If you fail to anticipate these perfectly normal reactions, the beast can quickly get the better of you. Bottom line, it could make you another statistic in LOC-I. Don’t be that pilot.

Some pilots like to use a mantra to help them remember the procedure, such as “Power Up – Clean Up – Speak Up” or “POWER – PITCH – PEDAL”. If a procedure like this helps you, use it or create your own. Communication is the last priority. On an IFR clearance, you are automatically cleared for the missed approach procedure. So don’t distract yourself until you are positively climbing and ready.

A procedure is a set of sequenced actions. Technique is how you execute those actions. I’ll discuss some good techniques below. Regular practice is how you make it a ritual.

First, you must anticipate the forces and reactions instead of reacting after the surprise. Be prepared to get busy, but do not rush the procedure. When aircraft power is changed, either increased or reduced, it is a destabilizing force on the plane. Couple that with a lot of nose up trim, and when full power is added, the reaction can be surprising.

The go-around can begin any time. If you start it in the flare or just before touchdown, a touch and go may result and it’s perfectly ok. Just remember to keep the plane tracking over the runway.

- Throttle: Smoooothly, deliberately apply throttle, especially in twins: an unexpected engine failure at this moment is a real handful. No need to rush and immediately jam it full open; you won’t like the reaction. Take about 2 to 3 seconds. By design the plane will pitch up when power is increased, plus it’s trimmed for the approach which needs a lot more nose up trim than a normal takeoff.

Furthermore, it does not take full power, even with gear and flaps full down, to simply level off. That is a lesson you should take away from Slow Flight practice. For example, at 4,000 to 5,000 feet, gear / flaps down and airspeed just above a stall, it only takes about 18 inches of manifold pressure [MP] to stabilize the plane in level flight!

- Pitch trim: Get on the pitch trim immediately to relieve the yoke pressure, which will be very powerful, to help you control the rapid pitch up. Once the power is applied it will likely not take much or even any additional elevator back pressure to achieve a climb attitude. In fact, you will most likely be pushing firmly forward. There is no need to initially begin a steep climb attitude, as the first effect of increased power will raise the nose enough to level the plane.

- Yaw: Prevent yaw. Expect it. Your reaction every time you need more power should be a habit of “Right hand forward—right foot forward” to stop left yaw. As with any lateral control input, some aileron will be needed to keep the wings level.

- Pitch attitude to hold: Know how high you want the pitch to go and don’t exceed that. Initially, just plan to raise the nose enough to begin a slight climb, usually about 4 to 5 degrees. Shortly in the sequence you will establish 7 to 10 degrees and hold it as you attain Vy or above.

- Clean up: Do not rush this step. When stabilized in your climb begin “clean up” — “call up” if necessary. Recall that communicating is at the end of the do list. When full power is applied, the plane will climb (or at least level off) even with all the drag devices deployed. To convince you, remember another take away from Slow Flight: Bonanzas and Barons will climb approximately 400 feet / minute at full power with all the drag out, even when airspeed is just above stall!

Flaps full down have approximately the same drag as the landing gear. It’s a toss-up as to which to raise first.

If your POH has a recommended sequence, follow that. When flaps are full down, I like to start them up first. Then I raise the gear because it moves fairly slowly. If you have the “approach detent” to stop the initial increment at half flaps, that works even better.Caution: Do not raise the final increment of flaps until the plane has a minimum 80 KIAS. Otherwise, the aircraft will stop climbing – or even descend – before that airspeed is reached.

- Adjust climb attitude: Make your final pitch and power adjustments. Most autopilot flight directors call for between 7 to 8 degrees. Ten up always works. Don’t forget once you are safely climbing, it’s also a good idea to move to one side of the runway, usually to the right, so that the pilot can see and avoid traffic below taking off. You wouldn’t want to miss seeing that Gulfstream climbing swiftly to intersect your belly.

- Check List: Finally, run your “after takeoff” or “climb” checklist, ensuring the mixture is set correctly for density altitude and the cowl flaps are open. Now choose where you want to go next.

The key here is to anticipate the aircraft’s reactions and stay ahead of them. Try using these techniques and I think you’ll be pleased with how nicely you can make a seamless transition from approach, even from a flare, to a climb at full power.

Fly the airplane each step of the way. Don’t be in a rush. Then you’ll earn bragging rights with the airport gang about how smoothly you performed your timely decision to balk the approach.

It takes practice and repetition to make this a ritual. A good routine is to perform the full procedure at least once a month. It doesn’t take long — and when you have the unexpected need to go around, your training, practice and confidence will kick in to make it a routine, safe maneuver.

Fly Often – Train Regularly – Practice More!

Hank Canterbury

ATP, CFII SEL & ME, MEI

FlyF33@aol.com